It’s been a bitter, blustery week in Wellington and I’ve heard several people make remarks like, “So much for spring!” and “This weather’s worse than winter!” Well, that’s because it still is; winter, I mean.

There are two views of the seasons in New Zealand. There’s the simple calendar folk who go, “1 September, spring. 1 December, summer. 1 March, Autumn. 1 June, Winter.” Then there’s the astronomical view. Personally, I prefer the latter.

A little history

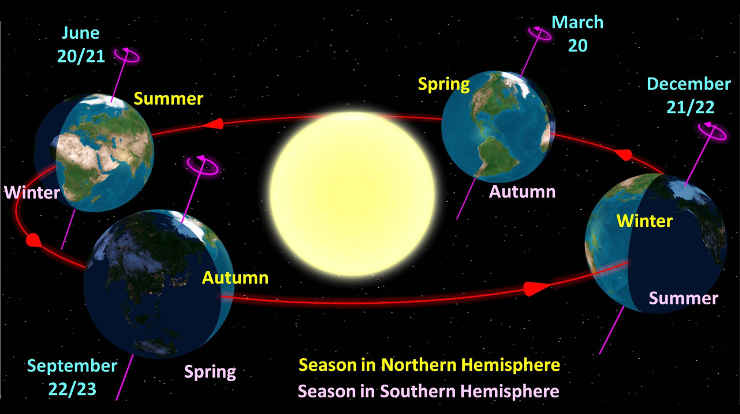

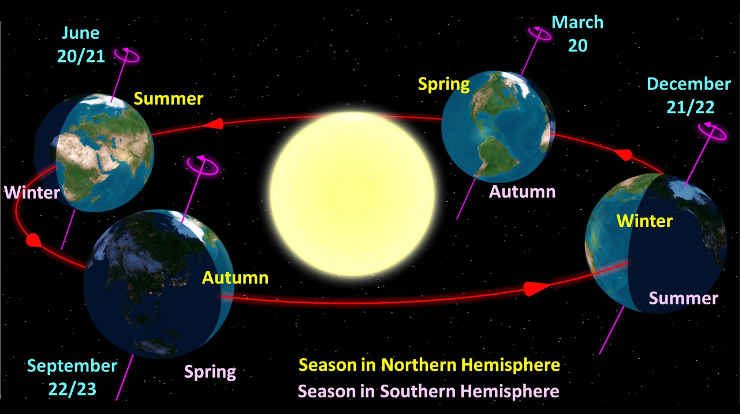

For millennia, the seasons have been defined by solstices and equinoxes. These came about because the ancients kept an eye on the sun, and the first thing they noticed was that in the colder months it didn’t rise as high in the sky as it did during the warmer months. By carefully tracking how high it rose each day, they were able to pinpoint when it reached its summer peak before getting progressively lower, while in winter months they marked its lowest point before it started going higher each day. They called these times solstice – from the Latin sol (“sun”) and sistere (“to stand still”) – because that’s what the sun appeared to be doing, rising to a peak (or a trough) before falling back (or starting to go up) again.

In terms of daylight duration, when the sun is at its highest point you get the longest day of the year, and when it’s at its lowest point, the shortest. Obviously, there are mid-points between those times, times when the number of daylight hours almost perfectly matches the number of night-time hours. The ancients spotted those too and called them equinoxes – again from Latin; aequus (“equal”) and nox (“night”).

Now you have the year divided up into the four equal periods we call seasons. The only problem is that those astronomical timings don’t neatly marry up with our calendar. Here’s how it looks in NZ for 2020:

Autumn equinox: 20 March

Winter solstice: 21 June

Spring equinox: 23 September

Summer solstice: 21 December

Two questions

That raises a couple of questions. First, why does summer solstice not mark the hottest day of the year – and winter solstice the coldest? After all, those are the days when the sun is at its highest (or lowest) point.

Planets are big things and they take a while to heat up, so although the sun is at its peak at summer solstice, the air is still warming and won’t reach its hottest till about six weeks later, at a point roughly between summer solstice and autumn equinox. (It’s the same reason that flicking on a heater in a cold room doesn’t warm the place instantly.) That puts high summer in New Zealand at the start of February and mid-winter at around mid-August.

Who cares?

That raises the second question: Who cares? It’s just dates after all.

Well, for a start, we’re celebrating things three weeks early. No one celebrates their birthday three weeks in advance or welcomes in the New Year on 10 December. And as this week’s weather attests, it really is still winter out there. But there are economic considerations too. Ski season in New Zealand typically ends when skiers stop going to the mountains, not when the snow runs out. Many of our mountains have at least some snow all year round, and I’ve actually skied Mt Ruapehu on New Year’s Day. The snow wasn’t great, but it was a novelty skiing in T-shirt and shorts for a morning, and we spent the afternoon playing golf at The Château.

Summer holidays typically start at Christmas when half the country races away to baches and beaches, only to return to work and miss the best, most settled weather in early February. Anyone who can remember sitting in sweltering classrooms when schools return during the hottest part of summer will know what I mean.

The main objection I hear to marking the seasons astronomically is that the dates vary because of leap years and certain other astronomical factors. Last year’s winter solstice was 22 June, summer solstice was 22 December, but spring equinox was September 23, just like this year. It’s too confusing!

Yet we live with other astronomical anomalies – like this year with its 366 days. And how’s this for an anomaly: How many weeks in a month? Four. How many months in a year? Twelve. How many weeks in a year? Fifty-two. Huh? As the Americans say, “You do the math …”

Me, I’m still looking forward to spring — which starts in ten days time.

Image credit:

By Tauʻolunga – Own work, CC0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=927625