My father died seven years ago today. A few weeks ago, a friend recalled the eulogy I read out at his funeral, an interesting tale of odd interconnections. Here, very briefly, is his story …

In the early part of the last century, somewhere around 1910, two brothers left England for New Zealand; Gus and Charlie Beecroft. They left behind a favourite sister, Louisa, who had recently married a London policeman by the name of Frederick Thomas Palmer.

In the early part of the last century, somewhere around 1910, two brothers left England for New Zealand; Gus and Charlie Beecroft. They left behind a favourite sister, Louisa, who had recently married a London policeman by the name of Frederick Thomas Palmer.

That was the first connection.

In 1921, Louisa gave birth to my father, the sixth of eight boys. As a youngster, Dad was fascinated by what he called “the pink papers” sent by his Uncle Charlie. Copies of the Auckland Weekly News were stored on the top shelf of the cupboard in his parents’ bedroom, and Dad would go up there, carefully take them down, and lie on the bed studying the strange place-names and photographs of a distant country; of mountains, snow and sheep.

That was the second connection.

His mother died when he was twelve. At fourteen he went to work as messenger boy for a grocery chain, and by the time he was seventeen he was a serving assistant in the Home and Colonial store Hornchurch, Essex. There Dad and his co-workers would receive 56lb cartons of butter and 80lb cheeses – two to a crate – in boxes emblazoned with a silver fern, sent from factories with exotic-sounding names like Tuakau, Waharoa and Ngongotaha.

That was the third connection.

Shortly after the outbreak of war in September 1939, the front room window of my grandfather’s house at 183 Lyndhurst Drive in Hornchurch sported the photographs of five young men. Each represented a son who had gone off to serve his country. By 1941 there were six when my father joined the Royal Marines, and a year later there were seven, though by that time two were wreathed in black.

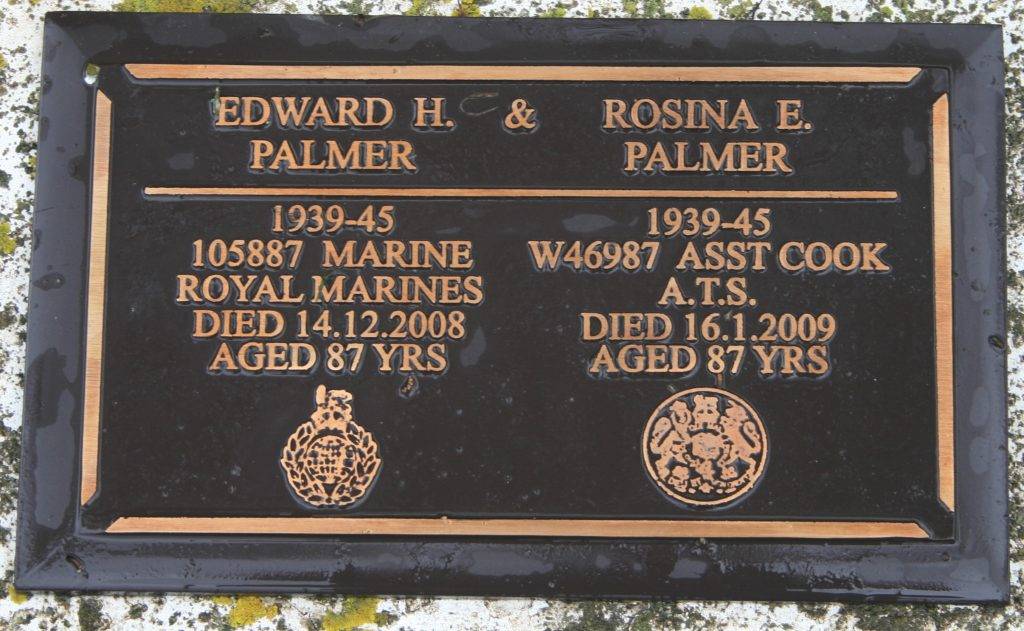

Dad served as a Royal Marine Commando during World War II taking part in a number of beachhead landings including Salerno in Italy, Sword Beach, near Caen in France, and Walcheren Island off the coast of Holland. It was there, on November 1st 1944, that he received an almost-fatal wound. A shell exploded near his landing craft, sinking it, and Dad was hit in the back by a knuckle-sized piece of shrapnel that missed his spine by a quarter of an inch.

That – at least obliquely – was the fourth connection.

When he was de-mobilized in 1946, he tried to follow in his father’s footsteps and join London’s police force. He was turned down because of his wound. So he tried the fire service, with the same result. At that point he concluded that if his country didn’t want him, he’d go somewhere that did.

In 1947 he emigrated to New Zealand, and not long after his arrival he took a train to Dunedin and met, for the first time, with the Uncle Charlie who – two decades earlier – had sent his favourite sister copies of the Auckland Weekly News.

But fate wasn’t quite done with him yet because, when he was in Dunedin, he not only met my mother – who had been born ten days before him and grew up less than half-a-mile from where he grew up in east London – but he started work with a printing firm called Coulls, Somerville and Wilkie. A few years later he was transferred him to Palmerston North to assist with the opening of their new factory on Tremaine Avenue, a factory that – amongst other things – produced labels for the New Zealand Co-op Dairy Company. Labels for their butter and cheese exports. Labels that bore the names of factories in places such as Tuakau, Waharoa and Ngongotaha.

* * *

My father was the last of ten, part of what is now an almost vanished generation. He grew up in a time before most houses had electricity; a time when only shops had telephones; a time when world travel was measured in weeks and months instead of hours.

Two of his siblings died in childhood: Althea, at two; Lenny, at eleven. Two brothers were killed in the war: Reg, a fellow Marine, on board HMS Hood and Gus, a Grenadier Guard, who died in northern Italy. Of the remainder, all reached a good age. Fred served in the artillery, Wylie in the merchant navy, Les in Burma, Cyril in the navy, and my aunt Sis survived Blitz.

Dad was a modest man. A man of great charity towards others but someone who rarely mentioned his own troubles. It’s only been in the last few years that my sister and I learned of the effects of that wound he received in 1944, effects that included a certain weakness, occasional pain and an area on one leg that had no feeling. It was only through the persistence of a the local RSA that he finally claimed a war pension – more than fifty years late. Even so, I think he still felt a little guilty in accepting it because, in his own words, “Others suffered a lot more than I did.”

He once told that when he came to New Zealand he really only wanted three things; a home of his own, a good wife and a good family. It may sound a little boastful coming from me, his son, but I think he was wildly successful.

Geoff Palmer

December 2008

Moving. Thank you.

Beautiful Geoff just beautiful I miss Pa Les lots wish I knew uncle Eddie more xxxx

So glad I today was one of the rare days I open Facebook My thoughts are with you

Great write up geoff your dad was lovely man and it was great pleasure to get to know him aswell as the rest of the Palmer glan.

God rest them all